I’ve unfortunately had little time to keep up with research-related blogposts, in part because of all the research I’ve been doing! But I’ve also been busy with some amazing teaching opportunities. In the last six months, I’ve had the chance to participate in experiential learning and project-based learning programs with WPI students in San Cristobal, Guatemala, and London, England.

I’m currently the Associate Editor of the bimonthly newsletter, STEP Ahead, for the Science, Technology, and Environmental Politics Section of APSA, and I wrote about my experience in Guatemala and reflections on experiential learning for our March edition, which I’m sharing below. More will follow on the London trip!

~~~~~

Experiential learning may seem like just another buzzword among higher education administrations as they try to offer a “unique” experience to prospective students. But the underlying principle – that experience forms an important cornerstone of learning and development – is not something to be ignored as a passing fad by political science educators. In our courses, we are inherently addressing student experience in the political realm: voting behaviors, public policy impacts, elections, etc. But how can educators develop “direct encounter[s] with the phenomena being studied rather than merely thinking about the encounter, or only considering the possibility of doing something about it” (Borzak 1981)? As the longstanding Civic Engagement track at the APSA Teaching and Learning Conference shows, there is a real interest in creating opportunities for students to engage in activities that lead to reflection and learning, especially out in the field.

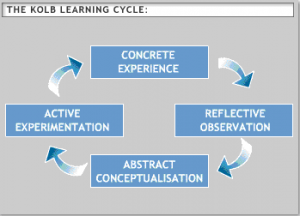

David Kolb’s book from 1984 laid out the basic structure of the experiential learning cycle:

Political scientists have already developed teaching resources focused on the experiential learning cycle specific to our discipline, including civic engagement and internship opportunities. And the recent presentations at the Teaching and Learning Conference reveal the range of experiential learning ideas that are shared in Political Science.

I became more interested in incorporating experiential learning into my STEP courses after I had the opportunity to serve as an advisor for WPI’s Engineers without Borders chapter (EWB-WPI). In January, EWB-WPI traveled to Guatemala for an assessment and monitoring trip for a rainwater harvesting project, which the group has been working on since July 2010. Although I was invited to join an existing project rather than developing it for students, the trip provided an excellent opportunity to see how field experience impacted student learning outcomes. In addition, I had the chance to enhance this engineering-focused project with social science considerations, including organizing and holding a discussion session on the social, political, economic, and health impacts of the rainwater systems on the community.

Although APSA has facilitated the collection of experiential learning resources, few specifically focus on STEP-related activities. And, unfortunately, my trip to Guatemala was an exceptional experience that I cannot incorporate into my courses or hope to duplicate in the future. Developing experiential learning opportunities also can take considerable resources, time, contacts, and institutional support. Yet, despite the potential hurdles, experiential learning opportunities are a wonderful way for students to get the real-world, “concrete” experience that Kolb encourages.